On the history of Tempelhof Airport

When SFU Berlin moved into its quarters in Tower 9 of the former Tempelhof airport building in autumn 2013, it was the first time that a university was founded on this ground, which is unique and highly historical not only within Berlin. This text traces the long and chequered history of a place that for over a hundred years was shaped by the political upheavals of the 20th century, by war, persecution, destruction, flight and the search for a new, safe home for millions of people.

Written in May 2019 by Ass.-Prof. DDr. Martin Wieser.

The beginnings – from agriculture to the airfield

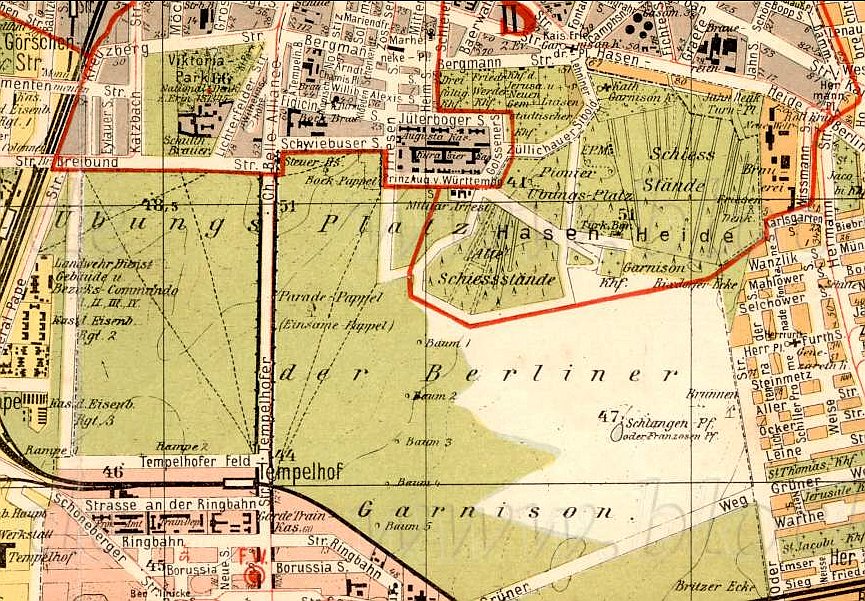

At the end of the 18th century, the “Große Feld” between Tempelhof and Schöneberg was converted from an agricultural area into a military parade and drill field under Friedrich Wilhelm I. The area extended westwards across Tempelhofer Damm and bordered directly on the north side with Hasenheide. At that time, the area extended westwards across the Tempelhofer Damm and bordered directly on the Hasenheide on the northern side. Over the decades, a horse racing track, a bathing lake and several sports fields were built on the site. Already at the beginning of the 19th century, the square was a popular recreation area for the Berlin population.

In addition to the military and the civilian population, the Tempelhofer Feld was increasingly used by aviation pioneers at the end of the 19th century to present their latest achievements: Hot-air balloons, zeppelins and finally the first motor-driven aircraft could be marvelled at on the field. In August 1909, Count Zeppelin arrived at Tempelhof with the airship LZ6 to the applause of 300,000 spectators. A few days later, Orville Wright made his rounds over the field and not only achieved a new altitude record of 172 metres, but also a record time of over 35 minutes of continuous flight.

In 1910, the field was purchased by the city of Berlin and parts of the site were rededicated for housing. In 1923, part of the undeveloped area was set up for air traffic for the first time and equipped with a runway, two hangars and a station house. In October 1923, civil air traffic began operations; by the end of the year, 150 passengers had already been handled at Tempelhof Airport. Air traffic increased successively in the following years and required further structural expansion measures. Nevertheless, part of the field continued to be available to the public for recreation. The US pilot Clarence Chamberlain landed at Tempelhof on 7 June 1927, setting a new long-haul record for the first transatlantic flight with a passenger from the USA to Germany. The Columbiadamm, which today lies on the north side of Tempelhofer Feld, is named after his aircraft, the Miss Columbia.

Concentration camps and arms production: THF after 1933

In 1910, the field was purchased by the city of Berlin and parts of the site were rededicated for housing. In 1923, part of the undeveloped area was set up for air traffic for the first time and equipped with a runway, two hangars and a station house. In October 1923, civil air traffic began operations; by the end of the year, 150 passengers had already been handled at Tempelhof Airport. Air traffic increased successively in the following years and required further structural expansion measures. Nevertheless, part of the field continued to be available to the public for recreation. The US pilot Clarence Chamberlain landed at Tempelhof on 7 June 1927, setting a new long-haul record for the first transatlantic flight with a passenger from the USA to Germany. The Columbiadamm, which today lies on the north side of Tempelhofer Feld, is named after his aircraft, the Miss Columbia.In addition to the military and civilian population, Tempelhofer Feld was increasingly used by aviation pioneers at the end of the 19th century to present their latest achievements: Hot-air balloons, zeppelins and finally the first motor-driven aircraft could be marvelled at on the field. In August 1909, Count Zeppelin arrived at Tempelhof with the airship LZ6 to the applause of 300,000 spectators. A few days later, Orville Wright made his rounds over the field and not only achieved a new altitude record of 172 metres, but also a record time of over 35 minutes of continuous flight.

As early as 1896, a “military detention centre” with 156 cells had been built on the northern edge of the Tempelhof field in Prinz-August-von-Württemberg-Straße (later incorporated into the airport grounds). From July 1933 onwards, this building, now renamed “KZ Columbia”, became one of the first scenes of National Socialist terror: throughout Berlin, SA, Gestapo and SS units combed Berlin shortly after the NSDAP’s “seizure of power” to rob, arrest, interrogate and torture Jews and political dissidents. Among the prisoners in the Columbia concentration camp were such prominent figures as Leo Baeck, Friedrich Ebert junior, Erich Honecker, and Ernst Thälmann. The “Columbia House”, run by the SS, mainly housed members of the SPD and KPD. In July 1933, 80 people were imprisoned here; three months later their number had already risen to 400. A total of between eight and ten thousand men were housed in this place, which functioned as a kind of “training centre” for later concentration camp leaders, such as Arthur Liebehenschel, who was assigned to Columbiahaus as a guard from August 1934 and became camp commander at Auschwitz concentration camp in November 1943. The successful escape of SS guard Hans Bächle with two prisoners from Columbiahaus in April 1935 attracted international attention. In Czechoslovakia, Bächle gave an interview in which he reported on mistreatment, beatings, torture methods and shootings at Columbiahaus. The international protests during the Olympic Games, which were held in Berlin in 1936 and were to be specifically exploited by the NSDAP leadership for political propaganda, but also the deportation of prisoners to peripheral concentration camps, finally led to the closure of the Columbia concentration camp in November 1936.

While political terror took place behind closed doors in the rooms of the former “military detention centre” after 1933, the adjacent airfield was used specifically for Nazi mass propaganda. More than a million people gathered at Tempelhofer Feld on the “Day of National Labour” on 1 May 1933 to witness the NSDAP’s first mass spectacle broadcast nationwide by radio. Like no other place, the spacious area of the field was suitable as a stage for the staging of Hitler and Goebbels. While the leaders of the workers’ movement were persecuted and imprisoned, the NSDAP leadership also usurped the holiday, which was originally intended to serve the international solidarity of all workers.

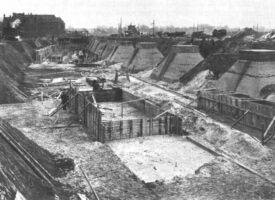

Although the hangars and handling areas of Tempelhof Airport had been continuously expanded and enlarged since the mid-1920s, capacity limits were reached at the beginning of the 1930s, which made it seem necessary to completely rebuild the airport into the “major airport” Tempelhof. The planning coincided with Hitler’s vision of the construction of a Reich capital, “Germania”, which was to reflect the National Socialism’s boundless claim to power in terms of urban planning. Under the direction of Göring’s Reich Aviation Ministry and the architect Ernst Sagebiel, planning began in July 1935 for what was then the largest building in the world in terms of area. The Columbiadamm concentration camp building was demolished in the course of the construction work in 1938. Today, a memorial at the Columbiadamm/Golßener Straße junction commemorates the victims of Nazi persecution in the Columbia concentration camp.

After the beginning of the war, production facilities of Weser-Flugzeugbau-AG and Lufthansa were relocated to the hangars at Tempelhof, although the construction of the building had not yet been completed (and could not be fully finished by the end of the war). Thousands of prisoners of war and forced labourers from Eastern Europe, mainly from Poland, the Czech Republic and Russia, were housed in barracks at the northern end of the field, where they were exploited under inhumane hygienic conditions for construction work on the site and for war production. As excavation work by the Institute for Prehistory and Early History at the FU Berlin has shown, remains of the barrack camps from this period can still be found under the surface of the field today.

As the city of Berlin was increasingly hit by bombardments, armaments production was relocated from Tempelhof. The fact that the new airport building had only comparatively minor damage was probably related to the fact that the Allies spared selected buildings from bombing to the extent that they could later be used to house their own soldiers.

Airlift and refuge: Tempelhof in the Cold War

After the end of the war, Tempelhof Airport was used as a military base in the US occupied sector of Berlin, and flight operations could be resumed as early as August 1945. Internationally known and still anchored in Berlin’s collective memory today is the establishment of the “airlift” in June 1948. After the blockade of West Berlin by the Soviet occupying power, which hoped to force West Berlin to surrender in this way, the entire population of West Berlin was supplied with many thousands of tons of coal and food by the “sultana bombers” of the Western powers until May 1949. To this day, the Airlift Memorial at Platz der Luftbrücke with its three struts commemorates the flight corridors of the three Western powers.

Even after the end of the blockade by the Soviet Union, Tempelhof remained a central theatre of the Cold War. The so-called “Green Barracks” on the west side of the site on Tempelhofer Damm was one of the shelters in the early 1950s for people from the SBZ/DDR who fled to Berlin and were to be flown out from there to the FRG. Although Tempelhof Airport was used as a military base by the US Army until 1993, part of the airport was returned to civilian use as early as 1951. Before the transit route was established, aviation was the only way to leave Berlin without being controlled by the GDR. Thus, even after the end of the “airlift”, Tempelhof became a scene of the global political showdown between East and West, but also of the fears, worries and hopes of those people who had become the plaything of these forces.

An end and a new beginning: Tempelhof today

The military significance of Tempelhof Airport quickly receded into the background after the fall of the Iron Curtain. The end of military use was finally followed by the cessation of civil aviation in October 2008. Parts of the listed building were renovated and occupied by the municipal administration and the executive branch, many smaller units are rented by various public, private and non-profit companies, projects and organisations, while the airfield has been open to the public for recreation again since May 2010.

In the wake of the rapid increase in the number of refugees as a result of the Syrian war in 2015, Tempelhof Airport once again became a place of refuge for people who had to leave their homes. For months, sometimes years, many hundreds of people were housed in makeshift accommodation in the hangars, where they had to wait for more suitable accommodation. Until the beginning of 2019, Hangar 1 at the airport was also home to the initial reception centre for new asylum seekers run by the State Office for Refugee Affairs. In addition, during the winter months, the cold aid, an emergency sleeping facility for the homeless, was set up in a hangar.

As a young university, SFU Berlin feels obliged to keep alive the memory of the Tempelhof airport site’s multi-layered past and at the same time to help shape its future: It reminds us of the social responsibility of the sciences – because they too made a significant contribution to the political and racially motivated persecution and expulsion of people who were held at Tempelhof. As a place of refuge for people who had lost their homes, however, the airport was and is also a place of rescue, of solidarity and fellow humanity, of voluntary and forced coming together of people from the most diverse backgrounds and biographies. As a space steeped in history and open to the future, Tempelhof Airport is faced with the opportunity to develop into a liveable, open and participatory space with a unique scope in the heart of Berlin. The challenge of shaping this space in the future while remaining aware of its history is not only incumbent on politics, but on all users, residents and visitors of the former Tempelhof Airport.

Further information:

Literature

- Auftrag Luftbrücke. Der Himmel über Berlin 1948-1949. Nicolai, Berlin, 1998.

- Vom Fliegerfeld zum Wiesenmeer – Geschichte und Zukunft des Flughafens Tempelhof. Quintessenz, Berlin, 2000.

- Appropriating buildings to house refugees: Berlin Tempelhof. Forced Migration Review, 2017.

- Die Utopie des Nichts. Zur Transformation des Tempelhofer Feldes in Berlin, dérive, 2011.

- Columbia-Haus. Berliner Konzentrationslager 1933-1936, Edition Hentrich, 1990.

Links

- Reich bebilderte Ansichten des Flughafengeländes: hier und hier

- Fragmente zur Geschichte des Tempelhofer Feldes im Nationalsozialismus.

- Initiative: Gemeinwohlorientierte Entwicklung des Tempelhofer Flughafengebäudes.

- Buchung von Führungen: Flughafengebäude und das Feld.